Explore how Dr. Manmohan Singh’s bold economic reforms in 1991-96 transformed India’s struggling economy. From liberalization to fiscal discipline, discover the policies that reshaped India’s financial landscape.

Dr. Manmohan Singh, India’s most educated Prime Minister, stepped into politics in 1991 as the Finance Minister. While his educational background speaks for itself, the reforms and policies brought by the bureaucrat in times of economic turmoil tell a story of its own.

The Indian National Congress came into power with P. V. Narasimha Rao as the Prime Minister of India. In June 1991, Rao chose Singh to be his finance minister. When he gained the ministry, India was in a bad financial state. He tried to push India out of this situation towards a better future.

Economic State of India in 1991-96

Singh’s ministry took the baton from the previously fallen government when the nation’s economic state was weak. The political instability led to a loss of international confidence in India’s economic management. Many such problems had brought the economic health of the nation to the corner.

With low foreign reserves (around $2500 million, sufficient to finance only two weeks of imports) and persistent current account deficits, India was unable to maintain foreign trade, and the economy was pushed to the brink of default. This forced the government to adopt emergency measures and seek assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The current account deficit was estimated to be more than 2.5% of GDP (around ₹675 crores) in 1990-91. The fiscal deficit also surged to about 8% of GDP due to government expenditures growing unsustainably on subsidies with questionable benefits, rising interest payments, and the low profitability of the public sector. A tax system riddled with loopholes and low revenue generation worsened fiscal imbalances.

Consequently, the persistent current account deficits had led to a continuous increase in external debt, which, including non-resident Indian deposits, was estimated to be around 23% of GDP by the end of 1990-91. By 1994, although the growth of external debt had slowed, it remained a critical area of focus. To avoid future vulnerabilities the budget emphasized prudent debt management by encouraging Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), reducing reliance on external borrowing, and planning to prepay high-cost IMF loans.

Additionally, the nation accumulated an internal public debt amounting to about 55% of GDP by 1991, substantially burdening the government. Interest payments alone constituted nearly 20% of total government expenditure, limiting the fiscal space available for developmental and capital expenditures.

The crisis was intensified by domestic political instability and global events, particularly the Gulf War. The war caused a sharp surge in global oil prices, putting significant pressure on India’s import bill and leading to higher foreign exchange outflows, as the country was heavily reliant on oil imports. This, coupled with growing uncertainty, resulted in a drastic drop in capital inflows, including commercial borrowings and non-resident deposits, limiting the government’s capacity to manage the situation using external resources. Domestically, resistance from various factions hindered large-scale reforms. Additionally, the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union disrupted longstanding trade relationships, particularly impacting India’s exports and bilateral agreements, which caused a sharp decline in export revenues, worsening the balance of payments crisis.

In 1991, adding to the precarious situation, inflation touched a whopping 12.1% for wholesale and 13.6% for consumers. The inflationary pressure was most acute in essential commodities despite good agricultural production. This paradox indicated deep-seated inefficiencies and imbalances in the supply chain and market mechanisms. The inflation rate peaked at 16.7% in August 1991. This was particularly concerning as it disproportionately affected the poorer sections of society, reducing their real income and purchasing power.

A significant challenge was the low productivity of investments and poor returns on past investments, particularly in the public sector. This inefficiency contributed to economic stagnation and the inability to generate sufficient internal resources for growth. The excessive protection given to domestic industries had weakened their competitiveness, resulting in inefficiencies, a lack of incentives for innovation and export growth, income and wealth disparities, and a disadvantaged rural economy.

Lastly, the financial sector (particularly the banking system) was under stress due to low profitability, poor asset quality, and inadequate provisioning for bad debts. Reforms were needed to strengthen the banking infrastructure and enhance its role in economic development. The 1992 securities scam exposed significant vulnerabilities in the financial system.

Key Proposals and Reforms in 1991-96

Faced with such bewildering economic problems, Dr. Singh made various reforms. Some of the reforms became historic.

Economic Liberalisation: Major changes were brought about by liberalizing the economy to open the country to the world for trade. A significant reduction was made in import licensing and exports were heavily promoted. Foreign Direct investment was encouraged and foreign equity participation of up to 51% was allowed in specified high-priority industries.

Liberalized Exchange Rate Management System (LERMS): The EXIM scrip system, which was used unethically to avail export subsidies burdening the government, was replaced by LERMS. Under this system, 40% of foreign exchange earnings would be converted at the official rate and 60% at a market-determined rate.

Public Sector Reforms and Disinvestment: Government spending was touching new highs and the public sector was not generating enough revenue. Consequently, disinvestment was highly carried out and up to 20% of government holding was proposed to be sold in selected PSUs. For restructuring, sick PSEs were referred to the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR).

Subsidy Rationalization: Subsidy rationalization, similar to disinvestment in PSUs, was directed to reduce government expenditure. Export subsidies were abolished in July 1991, saving ₹3,000 crores, while fuel prices were adjusted. Prices of fertilizers were raised and low-analysis fertilizers were deregulated.

Narasimham Committee: The financial sector was riddled with weaknesses. To counter that, the Narasimham Committee was proposed to study and recommend comprehensive financial sector reforms.

Higher flexibility to RBI: RBI was allowed more flexibility in setting interest rates to better reflect market conditions. Consequently, a reduction in Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) and floor level of interest rates was announced to increase the market money supply.

Capital Market Reforms: The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) was established on a statutory basis. Later on, central depositories were also formulated to enhance transparency.

Legalization of Gold Imports: The import of gold by NRIs and returning Indians was legalized, with an applicable import duty of Rs. 450 per 10 grams payable in foreign exchange.

Other Financial Sector Structural Reforms: Reforms like recapitalizing nationalized banks and restructuring Regional Rural Banks (RRBs) were taken. Recovery of Debt due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993 was passed, in 1994, for establishing Special Recovery Tribunals which aimed at the recovery of banks’ dues.

Corporate Tax Reforms: To compensate for the reduction in import and customs duties, the government initially increased corporate taxes and later streamlined them at a constant rate of 40%. An additional surcharge of 15% was charged.

Personal Income Tax Simplification: Income tax was simplified and tax slabs of 20%, 30%, and 40% were introduced. The exemption limit of income was increased to provide tax benefits to lower income groups and presumptive tax was introduced to simplify the compliance for small traders.

Expansion of Tax Deduction at Source: TDS was applied to commissions, bank interest on deposits, and high-value withdrawals. However, exemptions were provided to small depositors with income below the taxable limit.

Encouraging Tax Compliance & Revenue Collection: A voluntary disclosure scheme was introduced, which allowed tax evaders to declare unaccounted income. Along with the scheme, various measures were introduced to reduce tax evasion and increase filings.

Wealth & Capital Gains Tax Reforms: The application of wealth tax was limited to non-productive assets like property, jewelry, etc with the basic exemption of ₹15 lakhs. Long-Term Capital Gains Tax (LTCG) was reduced to promote investments.

Shift Towards VAT & Indirect Tax Reforms: Several steps were taken for transitioning to a VAT system to increase transparency. Custom duties were reduced excise duties were restructured, Modified Value Added Tax (ModVAT) was extended to capital goods and petroleum, and A 5% service tax was levied on select services (telecom, insurance, stock brokerage) to widen the tax base.

Conclusion

Surrounded by issues and looking for resorts to counter them, Dr. Manmohan SIngh presented a budget in 1991 that is often talked about. Subsequently, budgets following the 1991 budget, tried to undo the economic damage to India.

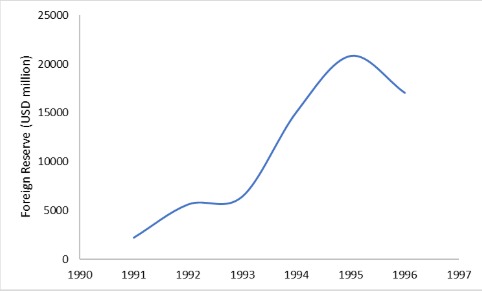

The most alarming issue of the unavailability of foreign reserves which was required to sustain the basic needs of the people was addressed strongly in the budget through the introduction of Liberalisation, Privatization, and Globalisation (LPG) policy and import compression. The steps taken showed a positive effect and the foreign reserves never dipped as they did before 1991 (Refer Figure 1). However, after 1992, the import compression was stopped to help the economy grow.

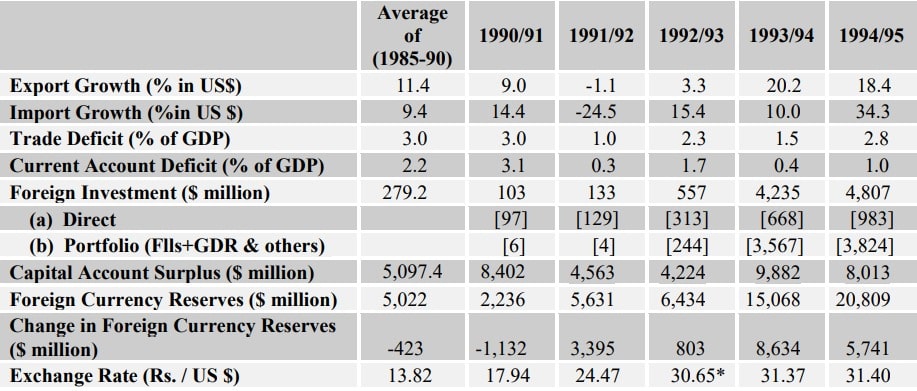

This import compression was aimed to solve another issue, i.e., the current account deficit (Refer Table 1). However, imports are not the only parameter impacting the current account deficit. The other factor is exports. Singh maintained that the policies adopted by the then government were meant to reduce the current account deficit. Certainly, the impacts were apparent and consistent with his expectations. A significant drop in imports (due to import compression) and a minor drop in exports effectively led to a manageable current account deficit (Refer Table 1). He might not have anticipated a decline in export growth, which is often presented as a criticism in discussions. Nevertheless, what we figured is that the exports were bound to be affected negatively due to the collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1991. Given that even after a decline in export growth, the current account deficit was reduced, is not a bad result for an economy that is on the brink of default. Further, none of the policies adopted by the Finance Ministry were directed to reduce exports and that is evident from the data of 1993-95.

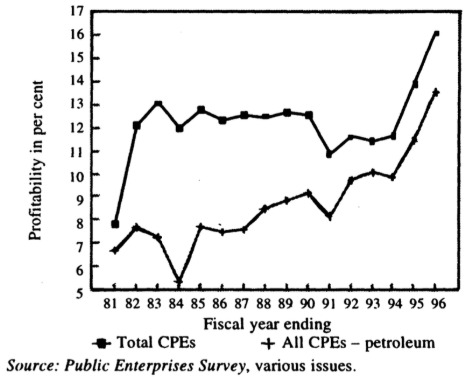

Another issue during that period was the fiscal deficit. One of the reasons for the high fiscal deficit was the uncontrolled government expenditure. Singh tried to control the expenditure by reducing subsidies and interest payments. He decreased the subsidy and consequently increased the prices of fertilizers to save the money allocated to the subsidy. This infuriated the public and there was nationwide disagreement. However, we believe the reasons he gave were logical as well as the need of the hour demanded such a step. Singh’s bold steps in reducing fiscal deficit were not just through expenditure control but he also kept in mind the other component playing a role in creating deficits, i.e., revenue. He focussed on increasing revenues by disinvesting in PSUs, referring chronically sick PSUs to BIFR, encouraging exports, and amplifying tax filing. The measures taken to improve the profitability of the PSUs showed a positive impact.

Another issue during that period was the fiscal deficit. One of the reasons for the high fiscal deficit was the uncontrolled government expenditure. Singh tried to control the expenditure by reducing subsidies and interest payments. He decreased the subsidy and consequently increased the prices of fertilizers to save the money allocated to the subsidy. This infuriated the public and there was nationwide disagreement. However, we believe the reasons he gave were logical as well as the need of the hour demanded such a step. Singh’s bold steps in reducing fiscal deficit were not just through expenditure control but he also kept in mind the other

component playing a role in creating deficits, i.e., revenue. He focussed on increasing revenues by disinvesting in PSUs, referring chronically sick PSUs to BIFR, encouraging exports, and amplifying tax filing. The measures taken to improve the profitability of the PSUs showed a positive impact (Refer Figure 2).

Analyzing the reforms chronologically, we feel that he prioritized expenditure control over revenue generation to contain fiscal deficit. This prioritisation could have been because he might be sure about the results of expenditure control while whether the revenue collection will grow or not is not a straightforward question to answer. Moreover, he wanted to review the recommendations of the committees formed to look into the tax system. After the recommendations, he made major changes to the income tax system.

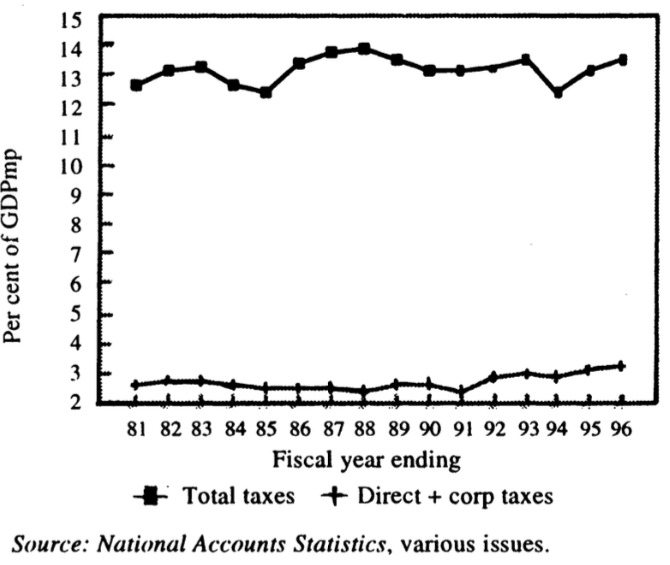

While the PSUs were turning profitable, increasing revenue. He brought about major reforms by introducing TDS and presumptive tax to aid low revenues as well as tax evasion. Furthermore, the income tax norms needed simplification. Thus, the structure of the old scheme of income tax was first seen in the budget presented by Singh. However, the efforts to increase tax collection were not very fruitful. The slow-growing tax collection is one of the quarrels analysts have with him. But what we believe is that the Indian economy was under the pressure of default and the revenue collection could have taken a back seat for a while. Maybe Singh also considered the economic health of the nation to be paramount and tried to restore it first rather than worrying about such complaints. His focus might not be to increase revenue but to reduce tax evasion. If he reduced custom duties or import duties, he compensated the decrease from other factions but still kept in mind not to burden a section of the public. This largely kept the revenues at a constant level (Refer Figure 3).

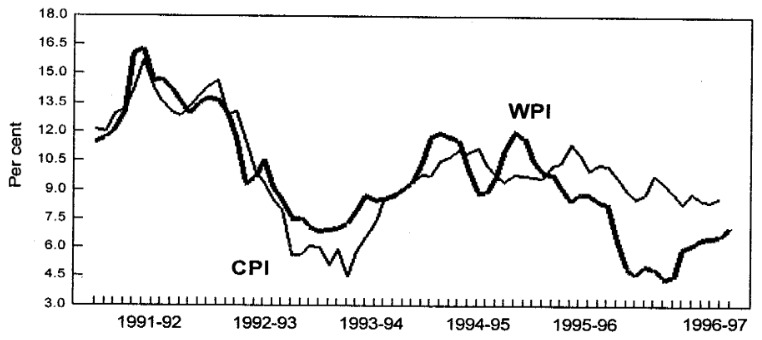

High inflationary pressures always kept Dr. Singh on his toes. While the factors involved in estimating inflation are complicated, we can analyze the data after the initial reforms were passed to see the results of those and the implications of those reforms on inflation. We observed that the ministry wasn’t able to bring inflation to its target level and the level before 1991 throughout its tenure (Refer Figure 4). High inflation burdened the poorer section immensely. However, with so many reforms related to export, import, financial sector, capital markets, and revenue, it might have been hard to anticipate which direction inflation would take a turn.

Additionally, external and internal debt was increasing at a decreasing growth rate. However, for a developing country with a fiscal deficit of 6% of GDP, it is hard for the government to reduce debt.

Concludingly, Singh carried India out of an economic adversary on his shoulders. He made India stand on its own feet while it seemed almost surreal in 1990. Even so, he was not able to meet the idealistic expectations in many places like inflation, debt, and growth rates. We understand it is wrong of us to ask a human being to solve all our complex worldly issues. Nonetheless, from an Oxford doctorate and the man of his cadre, we expected relief on all fronts somehow.

Leave a Reply